Image 1 of 3

Image 1 of 3

Image 2 of 3

Image 2 of 3

Image 3 of 3

Image 3 of 3

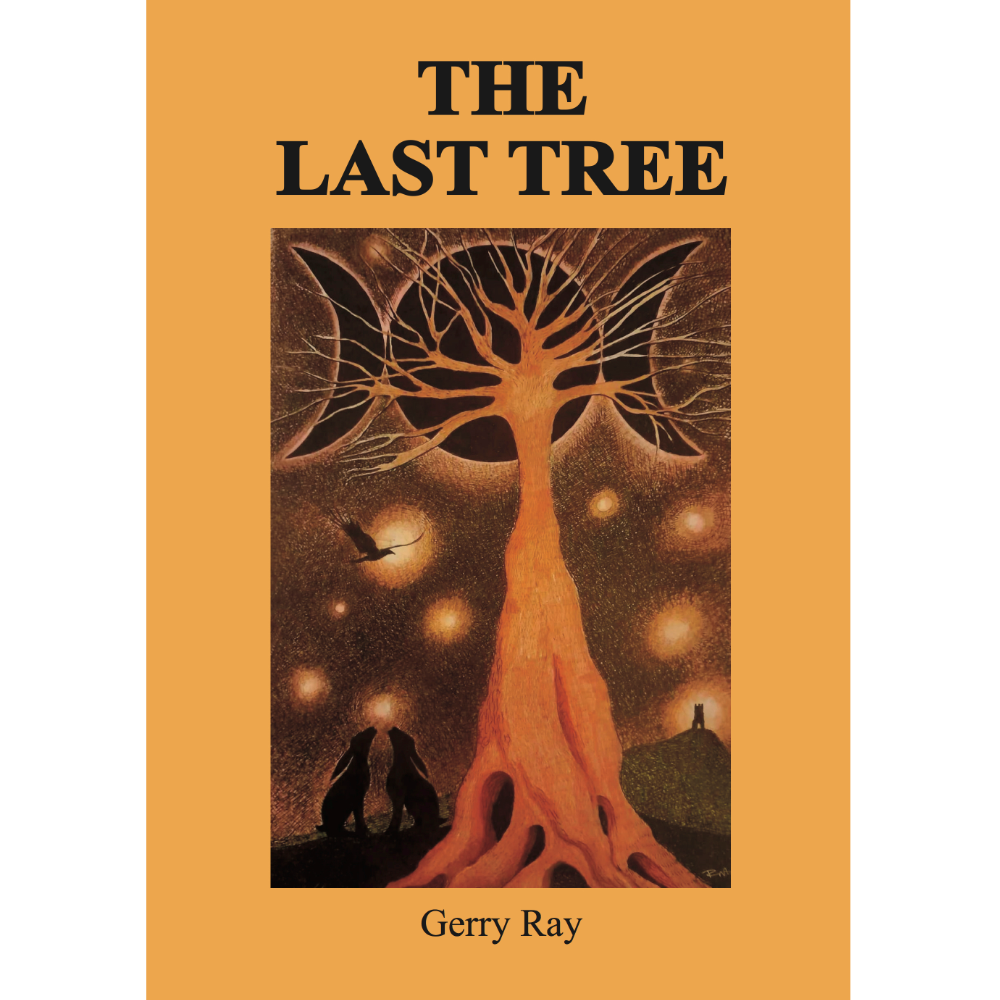

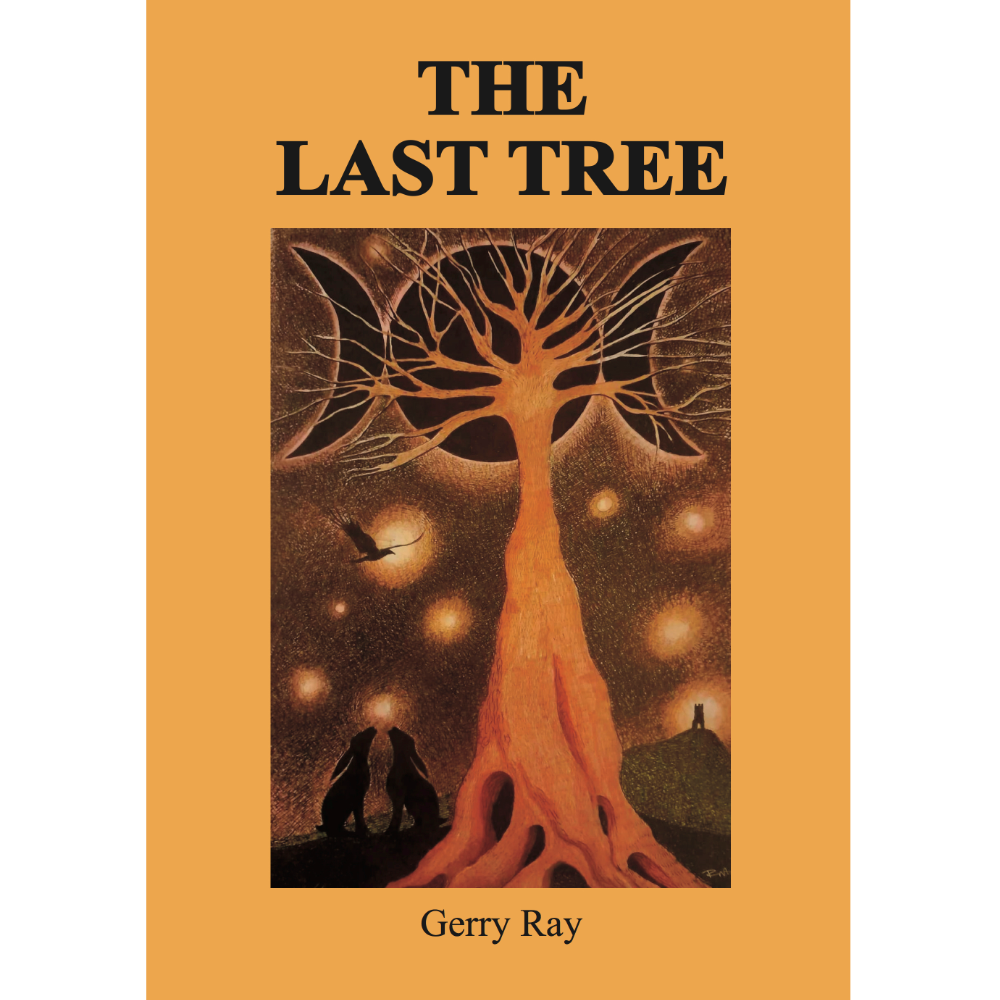

THE LAST TREE | Gerry Ray

Gerry Ray is unrelentingly willing (and able) – with words at least – to face and name life’s horrors, adjacent to its joys. He sees his love for and the steady loss of our planet as being closely associated with the fragility of human relationships, repeatedly seeking his answers in nature’s “strange garden”: “What do the eyes like starfish see? / What of the silent anemone?”. Birds, in particular, are observed both for their own sakes, as well as as metaphors, “falling from the sky like a sign”.

Nature – his religion – is sometimes observed and ‘real’, and sometimes “somewhere / in the mind”, “a tale … hatched / from a seabird’s egg”. But it’s often an unreliable muse: “the minstrel finding solace / in the appearance of words / or not?” And his writings buttress his examinations (as all poetry does) mainly of himself – his hopes, his pains, his regrets. However, like Richard Price in Gerry’s powerful series of poems dedicated to the eighteenth-century radical political philosopher and mathematician, he also dreams of “a kingdom / unfettered by Word”.

Much of what we read here rages against the horrors inflicted upon our fragile planet and its inhabitants [“I could taste two bloods in my mouth”]. And his association is always with what he sees as nature’s pacifism: the swallows of Kabul rising above human violence and excess; Tata Steel pumping “CO2 into the arid air” while wind surfers glide “as serene as summer gulls”; “the whale’s neck broken by man”; “Inuit dancing around dying embers”; “a polar bear on a shrinking icecap / or a Bengal tiger on a carpet of dust”.

And his extensive travels, both by public transportation as well as through the imagination – from his native Porthcawl to Palestine, from long-dead Silurian tribes to the people of south Sudan, from Merthyr Tydfil to the moon – have led him to associate events like the felling of the ancient Sycamore Gap tree in Cumbria with atrocities in Gaza, in Israel and Ukraine; and to write and campaign against war and for a new set of relationships based upon co-operation and care. His subject – however well hidden – is broken lives within the broken world he evidently loves so much … although the creator of these poems clearly holds out much more hope for the earth than for its human inhabitants:

For this land is a mortuary

for puerile bodies

and ancient words

that make no sense

Many of the poems in THE LAST TREE were written during and after the pandemic years, and focus on childhood experiences, trauma, love and loss.

Time passes as the poet takes us on his personal journey ‘seeing into the self’ (when ‘the first eye opens’), as he observes global events around him: war, extreme climate change, and impending extinction.

Artworks by Rhod Dawe.

Gerry Ray is unrelentingly willing (and able) – with words at least – to face and name life’s horrors, adjacent to its joys. He sees his love for and the steady loss of our planet as being closely associated with the fragility of human relationships, repeatedly seeking his answers in nature’s “strange garden”: “What do the eyes like starfish see? / What of the silent anemone?”. Birds, in particular, are observed both for their own sakes, as well as as metaphors, “falling from the sky like a sign”.

Nature – his religion – is sometimes observed and ‘real’, and sometimes “somewhere / in the mind”, “a tale … hatched / from a seabird’s egg”. But it’s often an unreliable muse: “the minstrel finding solace / in the appearance of words / or not?” And his writings buttress his examinations (as all poetry does) mainly of himself – his hopes, his pains, his regrets. However, like Richard Price in Gerry’s powerful series of poems dedicated to the eighteenth-century radical political philosopher and mathematician, he also dreams of “a kingdom / unfettered by Word”.

Much of what we read here rages against the horrors inflicted upon our fragile planet and its inhabitants [“I could taste two bloods in my mouth”]. And his association is always with what he sees as nature’s pacifism: the swallows of Kabul rising above human violence and excess; Tata Steel pumping “CO2 into the arid air” while wind surfers glide “as serene as summer gulls”; “the whale’s neck broken by man”; “Inuit dancing around dying embers”; “a polar bear on a shrinking icecap / or a Bengal tiger on a carpet of dust”.

And his extensive travels, both by public transportation as well as through the imagination – from his native Porthcawl to Palestine, from long-dead Silurian tribes to the people of south Sudan, from Merthyr Tydfil to the moon – have led him to associate events like the felling of the ancient Sycamore Gap tree in Cumbria with atrocities in Gaza, in Israel and Ukraine; and to write and campaign against war and for a new set of relationships based upon co-operation and care. His subject – however well hidden – is broken lives within the broken world he evidently loves so much … although the creator of these poems clearly holds out much more hope for the earth than for its human inhabitants:

For this land is a mortuary

for puerile bodies

and ancient words

that make no sense

Many of the poems in THE LAST TREE were written during and after the pandemic years, and focus on childhood experiences, trauma, love and loss.

Time passes as the poet takes us on his personal journey ‘seeing into the self’ (when ‘the first eye opens’), as he observes global events around him: war, extreme climate change, and impending extinction.

Artworks by Rhod Dawe.

56 pages

Published 2024

Softcover

16.5 x 23.5 cmISBN: 978-1-0686806-0-1